Factfullness

Hello everyone! Welcome to my second post!

Well, you will notice it is a bit long and as you probably noticed, this is just part 1. I am trying to improve my writing skills to make it as interesting as possible, I hope you like it!

For my first real post, I’ll bring you a book I recently read and gave me a lot to think about. It is called “Factfullness – 10 reasons why we are wrong about the world and why things are better than what we think”

Why talk about it?

I am considered an optimist among my friends (Honestly, I agree…). That being said, I don’t think I am irrealistic and more often than not, when I discuss different world related subjects, the arguments and opinions everyone had were “pessimistic” compared my vision of reality. Of course, maybe it’s just because I have an optimistic view of everything and since I don’t have any evidence to back my beliefs up I could not express it as a fact. Then I found this book, where the author shows us where we are at as a society, the challenges we cleared and the ones up ahead. And he does it based on facts and statistics while revealing different instincts that sometimes makes us think the world is worse than it is.

I know, it is a bit ironic to write about the 10 reasons why things are better when we are fighting the covid-19 pandemic, a lot of countries are quarantining and the global economy will probably enter a recession period. But, the current situation does not erase the evolution humanity achieved and it’s worth talking about it!

Book review:

I know, it is a bit ironic to write about the 10 reasons why things are better when we are fighting the covid-19 pandemic, a lot of countries are quarantining and the global economy will probably enter a recession period. But, the current situation does not erase the evolution humanity achieved and it’s worth talking about it!

Hans was a specialist in international health, a counsellour for the World Health Organization and is famous for his TED talks with more than 35 million views. He was also a teacher of international health in the Karolinska Institute in Sweden. There, he noticed his students had a lot of misconceptions about the world even though they were supposed to be more prepared than the average citizen. You can also take the test suggested by the authors to see where you rank yourself: http://forms.gapminder.org/s3/test-2018 (he honest 😉 )

The questions you just (maybe) answered were made to around 12 thousand people in 14 “developed” countries in 2017. You can find the results in https://www.gapminder.org/ignorance/gms/. If you opened the link, you probably noticed the hypothetical comparison between us and monkeys, where the probability of them getting the right answer is 33% (each question is multiple choice with 3 options). So the monkeys would get 1 in every 3 questions right. Spoiler alert, we performed worse than the monkeys…

Why do we perform so bad?

The first hypothesis is that our knowledge is outdated. The people that taught us about the world have outdated information and we base our answers on that… So, the answer should be simple, update the knowledge! To do that he went on Ted and several other places to teach us where we stand and the opportunities that it brings. Despite his efforts, he started to understand that there was something more than just access to recent information. In 2015, talking at the World Economic Forum in Davos, in front of politicians, businessman, entrepreneurs, researchers, activists, journalists and United Nations top-level representatives he understood that it had to be something else. Because everyone in that room had access to the most recent data, they had counsellors to keep them informed and even then they got most of the answers wrong. Outdated knowledge was not the only problem.

So, a second hypothesis was born. The human being has an excessively dramatic view of the world and it is hard to change because that is how our brain works… The human brain is the product of millions of years of evolution and we have some instincts rooted that helped our ancestors to survive in small hunting and gathering groups. We jump to conclusions fast to avoid immediate danger, we listen to gossip and dramatic stories because it was our means of information, we want fat and sugar because those were our energy sources when we didn’t have enough food. But some of those instincts are not as helpful now that our lifestyle changed… The desire for sugar led us to obesity problems worldwide and we are now educating the population for the benefits of eating healthy to tackle the problem. In the same way, we can make an effort to understand and control other instincts we have that prevent us from viewing the world the right way.

That is why Factfullness was created! The best way to do so is with facts. We don’t need to memorise a ton of statistics a few things point us in the right direction. So, what instincts are we talking about?

The Gap Instinct:

Talks about our tendency to divide the world in 2. Developed countries vs developing countries, us vs them, rich vs poor, the hero vs the villain… you get the idea. The media know this and will take advantage of it with opposite takes as well. It draws us in! And to be honest, they should do the contrast sometimes, to raise awareness for certain problems. Unfortunately, the overuse of this method leads to the idea of a gap between two things and that leads to factually wrong conclusions.

There is not a gap between developed countries and developing countries. There is a spectrum where every country is slotted. As we can see in figures 1,2, 3 and 4. (The link provided as reference takes you to the page where I took the screenshots, there you press the play button on the bottom left and you will see the development of the countries throughout the years.)

These graphs are all made with the gapminder tools. And there is information that all of them have.

- The different colours represent the world regions. Green for the north and south American regions, red for the Asian region (Australia is included here), blue for the African and yellow for the European.

- Each circle represents a country. The size of the circle is proportional to the population of the country.

It makes no sense to categorize countries like China and the Democratic Republic of Congo together. It is too broad. There is no perceivable gap anymore, we notice a continuity and a tendency for every country to move in a certain direction. Of course, I or the author could have handpicked these examples and you should not blindly believe what anyone says. I encourage you to go to https://www.gapminder.org/tools/#$chart-type=bubbles and play around with it. You can change the statistics to education level, life expectancy, CO2 emissions or a ton of other statistics and compare the development of each country through the years.

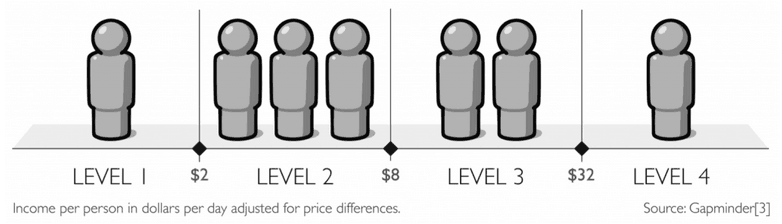

Hans proposes a new framework for how to think about the world, with four income groups.

Each level has certain obstacles that they have to face to clear to go to the next level (https://www.gapminder.org/topics/four-income-levels/). Almost like a video game… You can see it represented here:

Level 1 is the lowest and where all humanity started. Everyone in this level lives with less than 2 dollars per day, that is considered extreme poverty. Here you don’t have money for shoes and your main goal is to survive. The food is always the same, the one you can harvest from your farm and you have to walk for hours to have water. If you get sick there is a big probability you will die… In case you have a few good harvests, maybe you can sell some food in the market and get enough money to get into level 2. There are around 1 billion people like this. https://www.gapminder.org/fw/income-levels/income-level-1/

In level 2 you live with 2 to 8 dollars per day. You don’t struggle as much. The job is still physically demanding, but maybe you can save enough for a bike and use it as a mean of transport instead of walking. You probably also afford electricity and, although unstable, your children can study and hope to have a better life. You can afford some medication, but if a critical illness or extreme weather comes, you could go back to level 1. Around 3 billion people live like this. https://www.gapminder.org/fw/income-levels/income-level-2/

People on income level 3 earn between 8 to 32 dollars per day. Now you can afford to buy things beyond the basics. You have a cold water tap, more meal variety, maybe a fridge, a motorcycle or a laptop if you save for those things. Around 2 billion people live like this. https://www.gapminder.org/fw/income-levels/income-level-3/

Level 4 is most likely what you are used to. Earning more than 32 dollars per day, you have warm water, you can go out and ear at restaurants, you have an internet connection, etc… You have a car or other public transport, access to medication and advanced medical treatments. 3 dollars per day will not make the same difference in your life as it would for levels 1 and 2. Around 1 billion people are living like this. https://www.gapminder.org/fw/income-levels/income-level-4/

Go to https://www.gapminder.org/dollar-street/matrix to view pictures illustrating the 4 levels of income and more information.

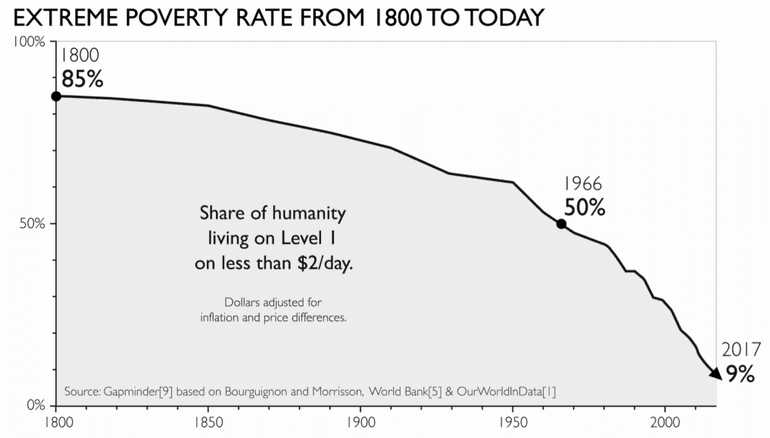

We all started in level 1… 200 years ago, 85% of the population was on level 1, and to generate more income and go up to levels 2, 3 or 4 it usually takes multiple generations. Nowadays, most of the population is distributed between levels 2 and 3 and are growing to higher levels. There is no gap… It is a broad spectre that is converging to higher income levels. So, every country should be defined by the level it is at instead of just saying developed or developing countries…

Ok, now that we know what the gap instinct is, what can we do? How can we identify it?

3 things usually trigger our gap instinct. The comparison of averages, the comparison of extremes and the “view from up here”.

- The comparison of averages is dangerous because the average hides a spread of numbers in a single one. They are super useful! But sometimes give you an image that does not correspond to the real picture and lead to wrong conclusions. Take this graf as an example:

If you only pay attention to figure 6, you might think there is a big gap between the two countries in terms of income. But looking at figure 7 there is considerable overlap between both countries. On average people do earn more in the US, but there are many Chinese and American citizens in the same economic situation as well. (The size of each curve in figure 7 represents the number of people living in that country.)

The comparison of extremes is an appealing one. It is good to raize awareness for inequalities, but usually does not help us comprehend the state of a country. There are always people on both extremes, some at the top and some at the bottom, but the majority is usually somewhere in between and only if we take that into account can we measure accurately the development of a country. Don’t just look at data from both extremes and draw a conclusion, look for the progression and what is in between those extremes. That way, the gap that the extremes paint will likely disappear.

Last, but not least, the “view from up here”. Hans compares this to standing on top of a skyscraper and looking down to the city. All the other building look short whether they are 2 stories or 10 stories high. It is a challenge for people on level 4 to understand the differences between levels unless we know what to look for. But someone on level 2 knows life is significantly better than in level 1. To know what to look for you can head over to the “Dollar Street” and see the differences between levels of income. https://www.gapminder.org/dollar-street/matrix

In Conclusion:

- It is easy to feel there is a gap when we divide the world or anything else in two parts. But most times there isn’t. Putting things in context, educating our selves and assuming there is always something relevant in between what is shown will help you control this instinct.

The Negativity Instinct:

This instinct describes our tendency to notice the bad more than the good. It is easy to think the world is getting worse as time goes by… All the terrorism, global warming, wildfires, a global pandemic… we have a lot on our plates! But is the world getting worse, better or is it staying the same?

- Well, Hans decided to ask that question and in almost every place, more than 50% of the people said the world was getting worse! https://www.gapminder.org/ignorance/mega-misconceptions/getting-worse/ (for some reason the link is not working. I hope when you click on it they already fixed the issue!) Turns out, the world is getting better… We are better than we were 20, 40 years ago and one of the prime examples is the extreme poverty rate!

The same way the extreme poverty rate is going down year after year, the life expectancy is going up, fewer children are dying before reaching 5, the average price of solar panels is going down, there are almost no plane crash deaths anymore, 90% of the population has access to electricity and water consistently, more than 65% of people have a phone and more than 50% use internet, the number of children with vaccines is around 90% (40 years ago was 22%…) and there are a ton of other incremental improvements that we can see in our day-to-day but make a difference in the long run. You can see a list of 32 improvements that the author decided to list here!

So, what is the Negativity Instinct based on?

3 things contribute for it: The false memory of the past; the selective reports from journalists and the activists; the feeling that since things are bad it is not right to say that they are improving…

We should be careful about our “rosy past”. We are so focused on our day-to-day, so adapted to the lifestyle we are in that we lose track of how things were in the past. It is not uncommon for people to say that things were better in the past, but that is because, most likely, they are misrepresenting the past. I become aware of this when I talk to my grandparents. My grandfather once told me a story about how his mother went to the doctor with her child on top of a donkey. The doctor was 10/15 km away and that was the only way. 10 km does not look like much, nowadays if I want to go to the doctor I get inside my car and I am there in 10 minutes. But 80 years ago she had to travel for more than an hour to get there. This reality is not intuitive to me… Even in my life, during my childhood, I didn’t always have warm water to shower and now it is something I take for granted… It is sometimes difficult to recall the past like it was and put things into a context…

The selective report is something we are all used to. Every time we turn on the tv we are exposed to an avalanche of negative news from all over the world. Wars, hunger, disasters, pandemics, death, corruption, unemployment, you name it. It is everywhere… The truth is that good news is not news… They rarely get reported, mostly because the good news is the norm, they don’t trigger our dramatic instincts, so they don’t have as many views as the negative news. If we report that no aeroplane crashed or that no child drowned it is just a normal day, but it is good news. Gradual improvements are something else that is not news. They are slow and unless you look for them, you probably don’t notice the improvements. But they are there… It is more likely to notice the dips than the overall improvement, but both are there. Remember that for every bad news, there are probably good ones that are not being reported as well.

Also, the media coverage is much higher now than what it was in the past, so, it is almost impossible for something to happen without it being noticed. That means there is a lot more exposure to the bad things of the world, which is good because applies more pressure for them to be solved. But is also bad, because it creates the illusion that things are getting worse and the society is deteriorating…

Lastly, some people feel it is unfair to say that things are getting better because there are a lot of bad things… The thing is, it can be bad, but better! Hans has a really good example to explain this:

Imagine the world as a premature baby in an incubator. “Does it make sense to say that the infant’s situation is improving? Yes. Absolutely. Does it make sense to say it is bad? Yes, absolutely. Does saying “things are improving” imply that everything is fine, and we should all relax and not worry? No, not at all. Is it helpful to have to choose between bad and improving? Definitely not. It’s both. It’s both bad and better. Better, and bad, at the same time. That is how we must think about the current state of the world.”

How do we fight it?

First, we can always expect bad news. Everyone that wants our attention will use our drama instincts to draw us in. If we are waiting for it and know that there is also good news that no one is talking about we can fight the negativity! And we can always look for the positive news, for example, we can look at statistics and see how things are evolving!

Then, maybe let us drop the “rosy past”… The past was difficult in every country and things are getting increasingly easier for everyone. I will use Sweden as an example in the graf below because it was the country the author used, but you can do the same with your country! And remember that the older generations like our parents, grandparents and generations before them had a much harder life and we would not be here without them!

They entered level 4 a few years ago, but there are still things to improve! And all the other countries are following the same path to the fourth level!

Well, this was the first part of my book review, I hope it was not super boring or dense. I am trying to be concise and still give meaningful examples. In the book, he talks about 10 different instincts and I plan to talk about all of them. If you have some feedback I accept it with open arms!!! I will leave the link for the Ted talks down below, feel free to watch them =)

See you next week,

Ricardo Ribeiro